The conflict in Syria has been called a civil war, proxy war, a regional conflagration, even a foreign conspiracy. These representations reflect a militaristic conceptualization of conflict that renders the Syrian people invisible and silences their intimate day-to-day lives.

Yet if we start thought from the life of an object – from the statues of ancient Palmyra to the mosaics of Apamea, from the paintings of young Syrian art students to the films of displaced refugees – what we uncover is a tale of genocide. As a record of existence, artwork allows us to trace the continuities of history and as such acts as an objective truth within a sea of conflicting ideologies. Thus, a story that follows the actions aimed at destroying these essential foundations of life makes it possible to untangle the complex politics of war and ultimately reveal that genocide is a collaborative effort.

Beginning in the early 2000’s, much of the art produced publically in Syria was closely tied to the regime of Bashar Al-Assad. While students could choose to study in schools of theatre, art, and music, opportunities to perform and discuss their artistic languages were nearly impossible, and creative potential remained hidden behind closed doors. With the March 2011 uprising came a new wave of artistic activity, propelled by both a strong political cause and an innovative social media network that dramatically changed global communication (artsfreedom).

Beneath the revitalization of art in Syria runs a cold and shadowy undercurrent. Artists and antiquities scholars have found themselves on particularly unstable ground as choosing to produce and preserve artwork brings them dangerously close to death. Syria has recently been called the “land of assassinated filmmakers,” as anyone with a camera or cell phone becomes an “instant target for sniper bullets” (Variety). A similar fate awaits those who defend some of the world’s oldest relics – relics that attest to the rise and fall of empires, and the development and spread of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. When Syrian scholar Khaled al-Asaad refused to lead Daash (the Arabic term for ISIS) to hidden Palmyra antiquities, he was beheaded. His mutilated body was then hung on a column in a main square of the historic sight.

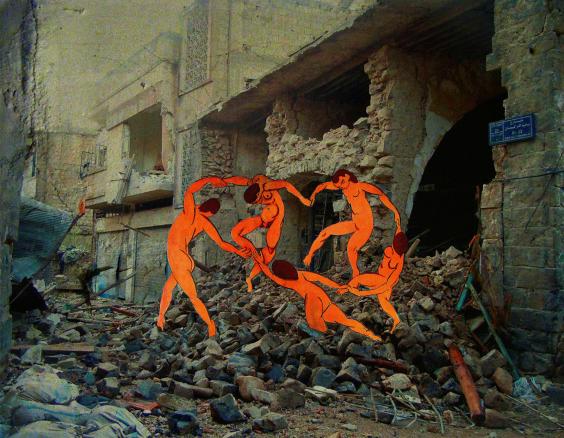

This is the world of art during a Syrian genocide. In this world, destroying artifacts is idolatrous, preserving ancient relics is apostasy, and the curation of antiquities is punishable by capital offence. To choose art, a universal affirmation of life, is to dance in front of death. Who is responsible for the death and destruction of art and those who defend its existence? Who truly values this artwork, why and when?

The media has bombarded the western world with Daash’s systematic and industrial campaign seeking to “take humanity back into prehistory” and establish its own caliphate (Guardian). Yet, until 2014 illegal excavation and looting was carried out by various armed groups, including individuals and the Syrian regime. It is only recently that Daash has joined the already existing practice, initiating a massive shift in the international significance of and concern for Syrian culture. There has been more discussion of looting and illegal excavation in the first month after Daash took control of Palmyra than there was in all of 2012, even with smugglers giving direct interviews about their trafficking of antiquities for and under the regime (Time). Why did the world not seem to care when President Bashar Al-Assad was bombing ancient museums, and now suddenly Daash is threatening our world heritage?

The sad fact is that the world does care. Yet, we can only care about what we know. Dominant knowledge in the western world comes from a media-complex concerned with sensationalized story telling rather than authentic reporting. Churnalism is a form of journalism in which press releases, wire stories, and other forms of “pre-packaged material” are used to create articles in newspapers and other news media without undertaking further research or fact checking (Wikipedia). This has become an increasingly pervasive problem in the reporting of illicit trade and political violence in Syria. News reports, as well as less official sources, recycle their way through popular culture, forming rigid patterns of collective knowledge. This rhythmic repetition of knowledge production perpetuates what Michelle Murphy calls regimes of imperceptibility. Regardless of whether fact creation is the work of scholars, journalists, propagandists or puppets, the production and reproduction of knowledge pronounces specific forms of information and obscures awareness of others.

Like white noise that drowns out unwanted sounds, power produces imperception by actively dictating which knowledge is knowable and which is not. While Daash is producing a geographical frontier upon which a new culture can take hold, Assad relies on a propaganda of rescue to eclipse knowledge that would otherwise cause him harm. Regime sources make claims to the “great work” of government authorities in returning looted antiquities (Reuters). Regime forces also claimed to have emptied Damascus museums and transferred artwork out of the city to undisclosed locations for safekeeping. Similarly ambiguous statements have been relayed by international media, including the UK’s Channel 4 News, Russia’s NTD TV, and the Seattle Times, proliferating the portrayal of Assad as the hero and Daash the villain.

Another argument around the politics of knowledge production can be made off of the headlines that notarized the regimes use of chemical weapons, while its use of starvation and cutting off of medicine has been pervading for years. Clearer, more objective accounts require stories from independently verified sources, yet Assad has sharply limited of the number of foreign journalists allowed entry into the country (Time). Even if allowed access, it is difficult if not impossible for journalists to investigate the peculiar cultural, political and economic heritage of the region –a deep understanding of which often makes cultural heritage professionals, like Khaled al-Asaad, exceptionally vulnerable targets. Thus, Daash remains the main perpetrator, and Assad slides elusively under the radar.

The bitter irony is that the wide media campaign of protecting cultural property is coming from a regime that is barrel-bombing cities and militarizing ancient archaeological cites to finance their failed economy. Responsibility for the country’s cultural destruction falls on all sides of the conflict. Abu Khaled, an archaeological guide who “dabbles” in antiquity smuggling during times of war, says that he has bought looted items from both sides. “Even the regime is dealing with antiquities, because they are collapsing economically. They need cash money to pay the shabiha [hired thugs]” (Time). Evidently, the illicit art trade is a collaborative effort that unites a murderous military in its attempt to salvage a disintegrating economy, Daash who wishes to destroy cultural identities and rewrite history, oppositional forces in need of weapons to fight back, and those who side with no one but simply need bread to eat.

For others though, the production of art is just as essential as its destruction. One response to the Syrian genocide has been a resurrection of creative expression and an outpouring of artistic activity. What is it like to be creative and expressive while surrounded by turmoil and unrest? What does it mean to create art and culture when ones country is drowning in armed conflict?

Artisan Tammam Azzam transports sensual images of love onto Syria’s destroyed buildings, contrasting the beauty of Syrian spirit with the brutality of war in an unfiltered expression of political dissent. The video sketches of Youseff Helali, Maen Wafte and Muhammad Damlacky satirize life under the “caliphate” and tell of the crushing of Syrian society by both Daash and The Regime through banners that read “same shit” (artsfreedom). These new, radical responses are based on the freedom to articulate ones own identity. The artwork is a politics of recognition – a rejection of dehumanization and a discrediting of Daash’s claim to “authentic Islam” (Guardian).

Yet, these images, films and scripts are not tales to distract, but rather deeply instinctual portrayals whose potency demands action. An artist is one who reveals and renders perceivable what the rest of us know only as ideas, thoughts or emotions. In his Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche argues “we have art in order to not perish from the truth.” I agree. Art does have a way of turning the conventional world upside down, of welcoming an indulgence in the freest of ideas and dreaming in the midst of disaster. Yet, there is more to art than that which allows us to break free from any existing philosophy.

Artwork is the purest expression of freedom and dignity, and a universal symbol of life, and in the case of Syria, revolution. Rev·o·lu·tion // latin – revolvere: to roll-back, or revolve.

Welcome to the artists’ revolution, where fire is fought with ice, and death with the creation of new life. This is not a set ideology, but rather a dynamic and evolving collection of ideas and behaviors that indicate a will to live, breath and tell a story of truth. Through the preservation and production of art, the people of Syria are reclaiming their rights and rescuing their identities. Thus, perhaps art itself is truth – a reflection of the intricacies of the human imagination and our unique capacity to meditate on things as they used to be, as well as dream of how they could or should be.

Artistic languages in and around Syria are generating a powerful and active citizenship that proposes its own guidelines and brings power back into the hands of the people. This revolution, sparked by the emergence of creative expression, is interacting with the wider world and shaping a self-conscious Syrian community, well aware that, even surrounded by death, art lives on.